The trailblazer who coined the term “documentary,” John Grierson (1898-1972) is routinely hailed the father of the form in both Britain and Canada. Yet, for someone who is so seminal to the genre, it’s curious how hazy this pioneering figure has become in modern times.

Though he initially popularized the word in a review of Robert Flaherty’s Moana (1926), Grierson’s own documentary filmmaking movement truly kicked off in 1929 with Drifters, a silent documentary about the North Sea herring fleet — his first and only quote-unquote personal film.

With the new montage style of Soviet cinema and the poetical style of Flaherty clearly influencing him, the feature, which first screened at the British premiere of Battleship Potemkin, contains many of the traits that would eventually characterize the documentary movement’s output. Specifically, the social interaction and everyday routine of the fishermen at sea, as well as the economic importance of the fishing industry, receiving special emphasis.

Successful both critically and commercially, Drifters wasn’t just widely hailed a response to avant-garde, Modernist films, but for aiming to make a socially-directed commentary on its subject. The film also showed that Grierson wasn’t the slightest bit hesitant to alter reality, as necessary, in order to have his vision shown.

Any argument for Grierson single-handedly establishing the principle of public service filmmaking begins with Drifters.

It could be that his legacy is less tied to a particular work or body of films — be it films he directed like Drifters or Granton Trawler (1934), or the 50-plus he produced and/or creatively contributed to — but rather the careers he influenced and the industry he helped create. Or, perhaps that his influence was so widespread in Canada that it’s difficult to point to a single moment that defined his career. But Grierson’s vision still continues to define the genre nearly five decades after his death.

One of the careers he helped shape was that of Alanis Obomsawin. The acclaimed Indigenous director embarked on a friendship with Grierson in the early 1970s, only a couple of years prior to his passing, back when he was teaching at McGill University. “There was a gathering of young students who would come and stick around Grierson to hear the things he had to say,” Obomsawin remembers. “Just by listening to him, you could learn so much about the history of filmmaking, especially documentary. I had a lot of conversations with him that I never forgot.”

In one of those exchanges, Obomsawin not only learned that Grierson’s father was headmaster of a school in Cambusbarron (a historic village in Stirling, Scotland), where he used films for instruction, but that his mother was also a teacher, and had grown quite distressed about the “people out on the street.” It bothered her so much that she would cook big pots of soup or stew, and then deliver it to the homeless herself.

“He came from a family that was very concerned about others,” Obomsawin elaborates. “About people, about wanting to serve and about wanting to improve life for those who had less. That really interested me in terms of his character.”

From an early age, both of Grierson’s parents had steeped their son in liberal politics and humanistic ideals, as well as Calvinist moral and religious philosophies, particularly the notion that education was essential to individual freedom. It was this upbringing that shaped his principles of documentary. Not just that cinema’s potential for observing life could be exploited in a new art form, but that the quote-unquote ‘original actor and original scene’ were better guides than their fiction counterparts when it came to interpreting the modern world.

Obomsawin recalls Grierson recounting his initial foray into the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Surveying the absence of trees, not to mention the utter lack of anything substantial growing there, he became transfixed by seeing the footsteps in the snow of the people who lived there.

“It was beautiful to come across someone who had a concern, who wanted to hear the voice of those people. That’s what I was very impressed with,” she asserts. “He really believed documentary was for the people, that it was their voice and it was for them to see themselves, and how they could come to know who they were and their story.”

Like Obomsawin, Marc Glassman, an adjunct professor at Ryerson University in Toronto, had the indelible opportunity to study under Grierson.

“A fierce Scotsman, he was a wonderful, contentious, brilliant and startling character, with piercing eyes and a gruff manner,” the editor, film programmer, writer and broadcaster reminisces. “He could intimidate you, but he wasn’t doing it out of fun. He was doing it because he wanted to understand the truth; how you perceived the truth to be.”

Grierson thought the first principle of documentary was to look at the real world and to open people’s eyes. And yet, at the same time, he wanted to see it crafted – for art, but in many cases, for public consumption – to persuade or instruct people.

“That really is the essence of his art and craft,” Glassman attests. “He didn’t necessarily want everything to be art. He thought that it was something he could use to prove a point in many cases. He also was very much about: What is the public purpose? What can we do with documentary that can help the world, or help a country like Canada?”

That public service remit had grown in Grierson over the course of several decades. He had produced his first film, Drifters, while employed as assistant films officer at the Empire Marketing Board (EMB) in London, a government body established in 1926 to promote trade and unity within the British empire through film, publications and exhibits. The film unit of the EMB would eventually move to the General Post Office, where he remained until 1937. (That same year, Grierson would contribute slow-motion footage to the Academy-Award winning film The Private Life of Gannets.)

Grierson first came to Canada in 1938, with the mandate to write a report on the Canadian government’s film activities. But, by 1939, he had drafted the bill to create the National Film Board of Canada, convinced Prime Minister Mackenzie King to fund it, and had been appointed to preside over it. (As of this writing, the NFB has released over 3,000 productions since its inception, while garnering over 5,000 awards.)

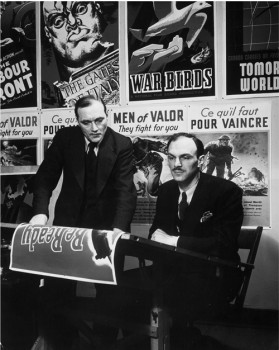

During World War II, King once again turned to him to serve as general manager of the Wartime Information Board – a body tasked with promoting patriotism and support of the war through the creation of posters, publications and other media. Ever the opportunist, Grierson saw the war as a vehicle for social change – a way that Canada could reinvent itself, and come out of the conflict with a deeper sense of national unity.

According to Claude Joli-Coeur, the current government film commissioner and chairperson of the NFB, Grierson was guided by two profound convictions: “First,” Joli-Coeur explains, “that documentary filmmaking has an unparalleled power for exploring real lives and issues – that it can be a powerful medium for advancing social justice and democracy.”

And second, “that Canada needs to be able to tell its own stories – that film is a way for us to span distances and cultural barriers, providing Canadians with a better understanding of who we are as a nation. As we mark the 80th anniversary of our founding, Grierson’s vision remains at the heart of the NFB mission.”

“The place has very good roots,” adds Michelle van Beusekom, the NFB’s executive director of programming and production: English program. “It has an incredible foundation, and that’s thanks to Grierson. Real filmmaking, real cinema, in Canada begins with the National Film Board. It begins with Grierson.”

For van Beusekom, what’s so important about that in terms of legacy is that, because of Grierson, filmmaking in Canada started as something unanticipated. Pretty much everywhere else in the world, it was about entertainment, about selling eyeballs to advertisers and making money. But, in Canada, filmmaking unequivocally originated as public service.

“Documentary was a way of knowing the world,” she enthuses, “of knowing your neighbour, of knowing the things that affected people of all classes and all walks of life across the country. Or, across the world, because Grierson never kept his eyes within one border. For him, documentary was the creative interpretation of reality.”

As such, van Beusekom believes there is a unique character to Canadian cinema, particularly when it comes to documentary, because it was really about this intersection of art and public service. She stresses the degree to which it has shaped Canada’s national cinema in a way that makes it tangibly different from other countries.

As for that aforementioned hazy understanding of Grierson’s legacy, Thom Powers, who has served as the documentary programmer for the Toronto International Film Festival since 2006, argues that one of the challenges to assessing Grierson’s career rests in how Grierson was more a facilitator, leader and theorist than actual director. Some of the most famous films associated with him, like Night Mail (1936), were actually directed by other people.

“I think we often study film history through the idea of directors as auteurs and as the signatories of artistic achievement, and Grierson doesn’t have that kind of body of work as the director,” he respectfully opines. Glassman agrees, claiming you could better define Grierson as an “auteur producer,” in that he was recruiting, challenging and developing standout young filmmakers such as Evelyn Spice Cherry, Gudrun Parker, Evelyn Lambart, Norman McLaren, Robert Verrall and Colin Lowe, to list only a few, in that period.

What’s more, with Grierson hailing from Scotland and helping invent the U.K. documentary industry before going on to set its Canadian counterpart in motion, no one can easily claim him as their own. It can be argued — and has — that if you’re a citizen of everywhere, you’re really a citizen of nowhere.

“Canadians are rightfully proud of his achievements, but he’s not going to be on a Canadian stamp. He’s not Canadian,” Powers points out. “And, as a Scotsman, people are rightly proud of what he went out and did in the world, but it’s not like he made his signature achievements there or in England.”

There are the enduring accusations that Grierson was overly didactic, too, and that he put Canada into a situation where it really didn’t develop a fiction film industry until the 1970s; that, to a certain extent, the country’s film industry has always been hampered as a result. However, while that might be worthy of debate, in gauging the lasting impact of Grierson, it’s all merely incidental.

“His driving force was to educate the public and to build a stronger democracy. He wanted people to know more, because he felt if they did, they would end up having a stronger sense of choice, and democracy would flourish because of that,” Glassman contends. “It was an idealistic perspective, one that I think some people still have to this day.”

Grierson saw film, and later television, as being tools for people to achieve greater learning. Or, as Obomsawin herself iterated at the outset, some level of being able to express who they were to other people.

“Today, we can see people all over the world using these tools,” Powers concludes, remarking on the documentary field’s recent growth in popularity. “It’s too bad he isn’t around to witness it.”

Story written by Chris Metler

Photos courtesy of the NFB