This article was originally published in 2010

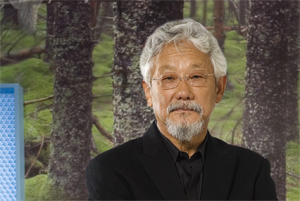

A prominent geneticist, eco-warrior and broadcaster, Dr. David Suzuki has spent over 40 years in front of the camera – and even longer in the classroom – educating the public about science, technology, wildlife and the environment. He’s hosted the CBC’s The Nature of Things series for an astounding 31 years and amassed legions of fans and followers, not only in Canada but also in the 40 countries where the series has aired.

Passionate and outspoken, he’s also distinguished himself as the guy who won’t back down from a fight; calling out government and industry for failing to protect the natural world.

And now, at the age of 74, Suzuki continues to be the country’s most well-known and beloved environmental crusader.

But this icon – voted fifth greatest Canadian of all time by CBC viewers – considers his star status a double-edged sword.

“I never got into show biz to be a celebrity,” says Suzuki. “I thought I was just the messenger: I’m going to present people with information and then they will go out and be empowered to do something about it.”

But it hasn’t turned out that way, he says.

“Instead, something truly remarkable happened. By watching my shows, viewers have empowered me,” Suzuki explains. “That’s a huge responsibility. I never signed up for that.”

Suzuki says he’s constantly approached by members of the public, who thank him for waging the battle to protect the environment. He finds this problematic.

“I want to say to them, ‘I’m one person,'” he explains. “We’ve got to get people to do more than watch [The Nature of Things] and say ‘I support Suzuki.’ It would be a huge conceit to think that one person or one program or one environmental organization is going to bring about change. We all have to be involved as part of a huge movement… that’s when I believe we will truly be powerful.”

Suzuki was first struck by the influence television can wield back in 1963 when he was asked to lecture in front of the camera for the University of Alberta series Your University Speaks.

“I was a hot shot scientist then,” says Suzuki, pointing out he grew up without a TV at home. “It never occurred to me that I’d have a broadcasting career.”

Suzuki gave eight lectures for this 8 a.m. Sunday morning broadcast and expected no one would watch. He was wrong. People on campus started to approach him, saying they loved it.

“And I’m thinking, what the hell are you doing watching television on a Sunday morning?” recalls Suzuki. “And that’s when I realized this is a very powerful medium to connect with and educate large numbers of people.”

With this in mind, Suzuki approached the CBC to let him make his own show – Suzuki on Science, a weekly half-hour series that aired in 1971 and 1972.

“I realized Canadians knew nothing about science and I felt this was really bad because they had to know what was going on,” he explains.

The show aired Sunday afternoons and often competed against football. Still, it developed a following, particularly among young people, because of the oddity of Suzuki himself, who was a hippie at the time, sporting long hair, a headband and granny glasses.

“People were shocked to see a scientist looking this way,” says Suzuki. “And a lot of scientists were outraged that I would go on air like that.”

After two years, Suzuki was hooked on TV – yet he quit the show out of frustration.

“It was basically a talking heads show and I wanted to do something more sophisticated to take advantage of the medium of television,” he explains. “We had no budget at all.”

In 1974, the team behind The Nature of Things, then a half-hour show, launched another 30-minute series, Science Magazine, and Suzuki – who by this time had made quite a name for himself hosting various radio and TV projects – was brought on board. In 1979 CBC merged the two shows and the hour long The Nature of Things with David Suzuki was born.

The environmental movement was just ramping up and with Suzuki at the helm, The Nature of Things – which previously had focused on natural history and science – became increasingly strong in its presentation of environmental issues.

“The public really responded because we didn’t hesitate to take on the logging or the mining companies,” says Suzuki. “Over and over our stories have galvanized the public. They look to the series to see what the problems are; and what we can do about it.”

Though scientists aren’t typically the best people to explain complex ideas in a simple and arresting way, Suzuki says his father, who had only a high school education, gave him sage advice that helped him hone that skill.

“My father was my biggest fan,” explains Suzuki. “He would call me up and say ‘Dave, that was a good program but there were all kinds of things I didn’t understand. And if I can’t understand it, as someone who loves you and wants to love your show, how do you expect someone who doesn’t give a damn about you to understand and watch your show?'”

But while he may not talk like a scientist, Suzuki’s academic background serves him well in his role as a journalist.

“I go into a lab to interview a scientist and they know I’m a scientist too so they can’t B.S. me,” he says, with a laugh. “It’s funny because sometimes they are very nervous.”

Suzuki has been involved in countless hard-hitting and award-winning science and nature documentaries, not only for Canadian broadcasters but internationally. He’s also authored more than 40 books and been recognized by the United Nations for his environmental leadership.

And yet he feels that his most important contribution is the foundation, headquartered in Vancouver, which bears his name.

In 1989 Suzuki’s radio series It’s a Matter of Survival sounded an alarm on the catastrophic future of the planet. Over 170,000 shocked fans sent him letters, asking for ways to avert the crisis. This led Suzuki and environmentalist Dr. Tara Cullis to create a science-based org, The David Suzuki Foundation, to find solutions to environmental issues and look for ways for humanity to live in balance with nature.

And he has his viewership to thank. Suzuki points out that much of the original start-up funding for the foundation came from the public. Over the years, he kept the names and addresses of all the viewers who had written him, and sent out donation requests when the foundation was launched.

While Suzuki has an ardent fan base, politicians, corporations and even other scientists have held a different view of the outspoken scientist.

Suzuki admits he’s a “pain in the ass” for governments and many industries – and, by extension, for the CBC.

“There has been constant pressure to pull us off the air and, to their credit, the CBC has never muzzled us,” he says. “They have stood by me all these years and I am eternally grateful for that.”

As a broadcast icon who’s been in the documentary game for close to four decades, Suzuki is pragmatic and knows that The Nature of Things has to evolve to keep up. And in an era where what’s new is hot and style often trumps substance, he says the fact that the series is still alive and kicking is truly a testament to its value.

“Any show that survives five years these days is a damn good series,” he says. “The Nature of Things has been on the air for 50 years. My God! That’s survival of the fittest.”

Photo courtesy CBC – G. Pacek