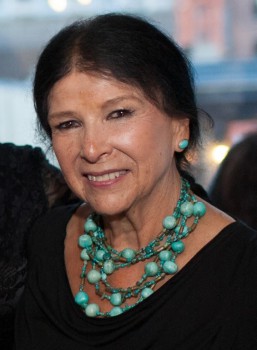

Obomsawin’s 2017: ‘I feel that Canadians are listening now’

Playback's Filmmaker of the Year completed her 50th film in as many years and spearheaded the NFB's plan to bring about representational parity for Indigenous creators.

It’s been seven years since Playback inducted filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin into its Canadian Film and Television Hall of Fame. In the time since, the Abenaki director/producer has shown no interest in lessening her workload, releasing five docs between 2012 and 2017, receiving a slew of accolades – both inside and outside of the film industry – and, most recently, world-premiering her 50th career film in 50 years at TIFF ’17.

It’s been seven years since Playback inducted filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin into its Canadian Film and Television Hall of Fame. In the time since, the Abenaki director/producer has shown no interest in lessening her workload, releasing five docs between 2012 and 2017, receiving a slew of accolades – both inside and outside of the film industry – and, most recently, world-premiering her 50th career film in 50 years at TIFF ’17.

She’d prefer you didn’t call it a career, though: “It’s more like a mission for me,” she says.

Premiering in the festival’s Masters programme, Our People Will Be Healed gives viewers an insider’s look at a school in the Manitoban community of Norway House, where students learn Cree language and Indigenous history alongside a more traditional curriculum. The film has since been named one of TIFF’s top-10 Canadian flicks of 2017.

And while Obomsawin has spent much of her career speaking out about injustices against Indigenous peoples, in 2017 she finds many reasons to be hopeful, especially with regards to education. “I’m always criticizing the education system, but now here I am praising it. I’ve never witnessed a school like this one,” she says.

The inclusion of Our People Will Be Healed in TIFF’s 2017 Masters category came three years after Obomsawin became the first Indigenous filmmaker to have a project in the programme with 2014’s Trick or Treaty. And that’s just the start of her successes: in recent years her projects have landed notable international sales, including We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), which sold to SBS (Australia) and APTN and Hi-Ho Mistahey! (2013), which sold to Netflix (Canada), SBS (Australia), TV Futura (Brazil), as well as CBC and TV5 Quebec.

But it’s more than her critical reception that has helped Obomsawin stand out in 2017. This year the National Film Board (NFB), which Obomsawin joined in 1967, unveiled its three-year action plan to bring about “institutional transformation” by creating more opportunities for Indigenous creators across all sectors of the industry – an initiative spearheaded by the Montreal-based filmmaker. As part of the transformation, Canada’s public producer also vowed to achieve representational parity across its workforce by 2025. Her involvement is further evidence of a career spent leading the charge for Indigenous filmmakers, paving the way for future generations.

Claude Joli-Coeur, chairperson, NFB, says Obomsawin has been an inspiration to both himself and the rest of the organization, influencing the NFB’s entire staff with her films, stories and determination to affect change.

In recent years, Indigenous youth have increasingly become a focus of Obomsawin’s work, as she examines the potential education has to make a better future for younger generations of Indigenous peoples. Our People Will Be Healed is the latest in a cycle of five films that focus specifically on the rights of Indigenous youth beginning with 2012’s The People of the Kattawapiskak River.

Joli-Coeur says that while Obomsawin has not been the sole reason for change in regards to the education of Indigenous youth, the power of her films to consistently expose untold stories has played a crucial role in giving a voice to the plight of Canada’s Indigenous population.

He is also quick to praise Obomsawin the producer, as well as Obomsawin the writer-director. While the NFB finances all of her films, Joli-Coeur says the on-set trust she builds with the subjects of her docs is a role that would traditionally be associated with a producer. “It’s that duality of role that gives these projects such a special perspective,” he says.

Another oft-noted facet of her filmmaking powers is the unrelenting energy and passion she has maintained since she first began. According to Joli-Coeur and fellow NFB colleague and publicist Jennifer Mair, working 12 to 14 hour days remains commonplace for Obomsawin, whose various mentoring, filmmaking and accolade-receiving responsibilities still demand so much of her time.

Outside the film industry’s parameters, Obomsawin has been recognized in various other capacities this year. In March, she received an honorary doctorate from McGill University’s School of Continuing Studies and was named among the first 17 recipients of the Order of Montreal, which honours individuals who have contributed to city’s development.

And the work is never complete. Though Our People Will Be Healed only premiered in September, Obomsawin is already at the editing stage of her next project, Jordan’s Principle, about a five-year-old First Nations boy, Jordan River Anderson, who died in a hospital from a rare disease amid provincial and federal squabbling over who would pay for his housing. Obomsawin hopes the project will be ready by early 2018. Another five projects are in various stages of development.

Obomsawin really comes alive when talking about the opportunities for Indigenous filmmakers in 2017, compared with her formative filmmaking years. “I really feel that Canadians are listening now, whereas before they weren’t interested. There’s room in every institution for Indigenous people who want to make their first film.”

And her appetite to continue her “mission” remains undiminished: “As long as I have my health, I will still be working. My passion hasn’t changed.”

This story originally appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Playback magazine

The definitive CDN broadcast and production resource.

The definitive CDN broadcast and production resource.