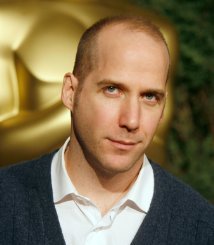

In the writer’s room: Michael Arndt

Ahead of the Toronto Screenwriting Conference this weekend, Playback caught up with Michael Arndt, the Academy Award winning scribe of Little Miss Sunshine and Toy Story 3.

New York based Arndt received an Academy Award in 2007 for his original screenplay Little Miss Sunshine and a nomination for best-adapted screenplay in 2011 for Toy Story 3. He shares a writing credit on The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013) and Oblivion (2013).

The Toronto Screenwriting Conference takes place April 5 and 6, 2014 at the Ted Rogers School of Management at Ryerson University.

PB: You broke into Hollywood with Little Miss Sunshine and recently the Tom Cruise-starrer Oblivion: how has the business changed since you first got into it?

MA: As a screenwriter in New York, my perspective on the industry is pretty limited. I know that a lot of people have a much better sense of the broader changes in the industry than I do. Nevertheless, one thing that seems to have changed is that it used to be that a screenplay would be written, and then the movie would get a green light for production based on that script. Now, increasingly, it seems that a movie will get a release date and a green light for production, and then a script will be commissioned based on that green light. To a writer, that may feel like putting the cart before the horse, but that seems to be happening more and more these days.

PB: You’ve become something of a go-to writer for big studios with a major franchise on their hands, whether for an original script or a good polish. What are some of the most important things you’ve learned working not only under the pressure of big studio budgets and mega fan expectations?

MA: The lesson I learned at Pixar on Toy Story 3 is that working on one of these big franchises is a team sport. There’s just no way I could have written the TS3 script on my own — it’s just too dense and narratively detailed. As the screenwriter on TS3, I was just one guy on a team that included the director, the producer, the story artists, and the Pixar brain trust of other directors and writers.

At this point, I feel like it would be suicidal as a writer to take on one of these giant projects and try to write the script entirely on your own. You just need other people there to give you feedback once you’ve done that first draft. If I have one talent as a writer, its in stumbling blindly into situations where I find myself working with people who are vastly smarter and more talented than I am.

PB: In your experience, what are some of the pros and cons of working on an established franchise or adaptation, versus an original script?

MA: The only real negative on a big franchise or adaptation is that you’re working from someone else’s idea. You don’t quite have the same sense of ownership. On the other hand, you tend to have an enormous amount of resources at your disposal. You have a director and producers who are going to help you resolve story problems. And a lot of times, the studio will have production designers or story artists who are already at work visualizing the story – figuring out what the world of the film looks like, both in terms of characters and locations. That’s a tremendous luxury to have as a writer because a lot of the unsung work a screenwriter does is coming up with locations that help tell your story for you.

On an original script, it’s the opposite situation — the story is yours and you feel complete ownership over it. The downside is that you have to do everything yourself.

PB: What is the number-one thing writers should know before accepting a gig on an established entertainment brand, such as Hunger Games?

MA: On Hunger Games, it was a dicey situation — they wanted a new draft of the script, but they were twelve weeks away from shooting, and they couldn’t push the start date because of the actors’ schedules. So there was very little room for error. The reason I said yes was that I had worked with Francis Lawrence on another project, and I’d had a really good experience working with him. But that seems like a commonsense rule of thumb for any creative project — try to choose your collaborators as carefully as you can.

PB: You famously started in Hollywood working for Matthew Broderick before breaking through with an Oscar-winning script for Little Miss Sunshine: what has surprised you the most about your success to date?

MA: The thing that’s surprising and kind of depressing is that I feel like, even now, I barely know what I’m doing. I have an okay sense of the craft of screenwriting, but the real art of screenwriting still feels elusive and foreign and baffling to me, if not completely out of my reach. The medium of movies is just infinitely deep — you always feel like you’re learning, so — in a way — you always feel inadequate to the task before you.

PB: What advice would you give up-and-coming screenwriters?

Be humble — seek out and listen to feedback from others.

Be patient — I wrote ten scripts before I got an agent and sold Little Miss Sunshine.

Aim high — try to pursue excellence (which is within your control as a writer), rather than success (which depends on others).

Be realistic — 90 percent of the work you do as a screenwriter will never see the light of day.

Try to stay in love with what you’re doing — we’re all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.

The definitive CDN broadcast and production resource.

The definitive CDN broadcast and production resource.